I built a terminal monitoring app and custom firmware for a desktop clock with Claude

The way that I've used AI for coding has changed drastically over the last year.

In fact, the rate at which it is changing is probably the most drastic element of it – I can't recall any time since my first year of college, twenty years ago, that I've experienced such a rapid evolution in my own ability to do stuff.

This week I have written a fully self-contained system monitoring daemon and terminal UI, based on the Charm toolkit and using DuckDB. It archives metrics to parquet, shows ECC status, SMART health, temperature, sparklines, historical charts, and even has an alerts system.

I am passingly familiar with Go, but this is a project that's been in the back of my head for a while, and would have been a monumental undertaking. It already works well enough, and I'm using it for a handful of servers.

Also this week, I built custom firmware to show Stripe subscription metrics for the Ulanzi TC001. I've linked to a good overview below if you're not familiar with it – basically a cheap and hackable desktop clock.

This is the kind of project I have dreamed about putting together, but I've never found the time required to become familiar with firmware development outside of a few Arduino demos many years ago.Most of these project ideas go to a list of ideas that I look at and go, "some day, if I have the time." – I rarely have the time. This blog was one such project, and I sat on it for ten years!

AWTRIX3 is the go-to firmware for customizing the Ulanzi TC001, but customization requires running a process on another machine and sending data over the network to the device. I wanted something I could bundle up and send to my other cofounders. So, again, I leaned on Claude Code to create custom firmware in Rust that communicates with the Stripe API, providing a subscriber count, MRR, and notification for new subscribers. It runs a wifi access point that you can connect to and configure, after which it connects to the wifi and communicates with Stripe via their API.

Ironically, given how long generative AI has been threatening art, I ended up having to do a lot of the actual pixel art for the device by hand. Precise pixel art is one area chat models remain mysteriously terrible at.

I have never written a line of Rust, but I know it is a relatively unforgiving language, and the ESP32 is a less forgiving environment than most I've developed for, with 8MB of flash storage and something like 160KB of RAM.

These are two projects that would have remained on the back burner forever, requiring activation energy that I just don't have to spare. They were both written over the course of a few days, here and there, between other work, and recovering from a cold.

#A year ago

When I was writing the engine that powers this blog in December 2024, I would upload a few files at a time through the Claude or OpenAI web UIs, try to get them to reshape them into something that seemed close enough to what I wanted, and then iterate on that work myself.

This was slow, but the project of putting together a custom editor using Lexical was daunting enough that I would not have attempted it otherwise. At that point I had only about six months of modern frontend development experience and my reach exceeded my grasp ...to paraphrase Robert Browning.

Then the startup I was working for ran out of runway, we shut down the company, I spent a couple of months learning Japanese, and then went bumming around Japan for a few months with my partner Ash.

Fast forward to August 2025, I'm starting a new company, and coding assistants are starting to generate a good bit of heat on Hacker News.

One of the first things I did after getting back was try to make some headway on my cofounder's MVP, and it seemed like a perfect opportunity to try out Claude Code. I had it write a few helper scripts, add logging, and act as a glorified find-replace in a few areas. For this tedious work it was quite useful, despite frequently giving up or failing the tasks.

I had it write the first draft of a feature that we needed, and iterated on it myself, getting Claude to throw in some fixes here and there.

Actually, it now reminds me of the accounts recorded by the engineers using the first computer being built at Princeton in the 1940s (from Turing's Cathedral, by George Dyson).

Essentially, the ENIAC often produced incorrect calculations, overheated and shut down during jobs, and was generally a hassle to work with. Despite all that, it was still better than doing it by hand, turning what would be months of human calculation into mere weeks of computer assisted work.

#December 2025

By December, I had written one major piece of functionality with Claude Code. Arguably I would have done a better job doing it by myself, maybe in a similar timeframe if I had been really dialled in and had no distractions.

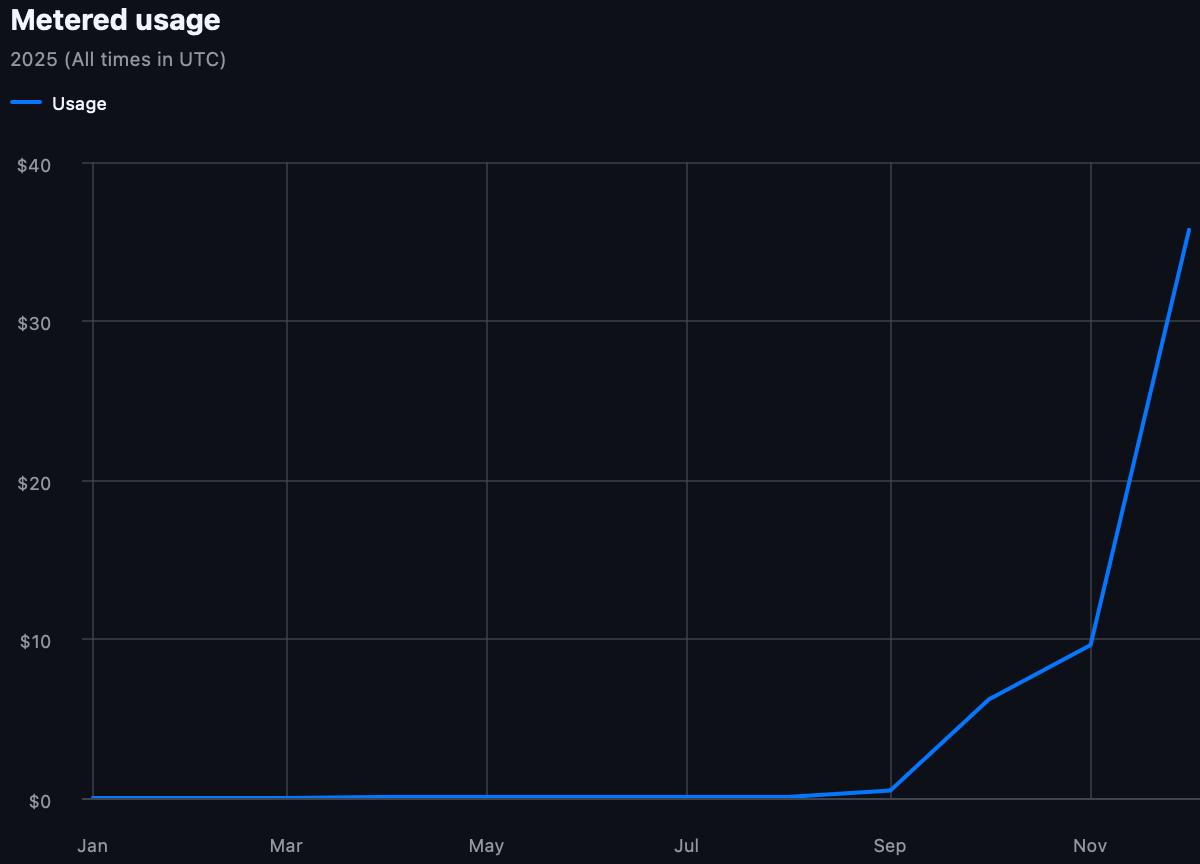

All of my experience was with Sonnet at this point, and while it was useful and sometimes surprisingly good, it wasn't a huge accelerant. If pushed, I'd have said something like 1.5x, maybe. My €22/month usage plan was enough to help me write helper scripts and break ground on new features though, which was already worth it.

At the end of November though, Opus 4.5 had been released, and some time in December I decided to give it a try. It didn't seem massively different at first, but I was still working with it like it was Sonnet – giving it small tasks, writing scripts, etc. It absolutely burned usage though, and until Opus I had never run into a limit before my usage counter reset. I literally didn't even realise there was a limit.

It wasn't until I started asking it to implement features that I found it was making far fewer mistakes, and was in fact producing relatively good first passes.

In October I had begun adding Github Copilot to some pull requests, and it had found a few issues. This was great, even if it came with some mistakes and noise. When you're a team of one and a half developers, an extra set of eyes is absolutely worth the trouble.

Eventually the Co-authored-by: Copilot notes start showing up more frequently in the commit logs, and I found it useful enough to pay for the basic subscription once my free tier limits ran out.

By the end of December, I was hitting my Claude Code limits constantly. I started using "extra usage" which lets you spend a little more to get to the end of whatever was being worked on when the included limits were reached.

I experimented with using GPT-5 and Opus via the Copilot extension included with VSCode. Once I run through the limits there, I start going through extra usage on that.

Using Copilot, I built the first application that I have not read line-by-line, a VAT invoice generator. I needed to generate mock invoices to do some basic interactive testing of the OCR flow for Manano. As long as it generated something that looked plausible, it was fine, but I found that with GPT-5 doing the bulk of the actual coding, I was able to freewheel on ideas about design and local-first software.

I wanted it to be like Tiddlywiki, where it could be used as a file on the desktop as easily as something at a URL. I wanted it to be WYSIWYG rather than a set of dull forms to fill out. And having a bunch of visually distinctive templates to make sure a variety of visual styles would work.

#Christmas break, structured prompts

Over the Christmas period, while Ash was visiting her family, I had the opportunity to get stuck into the feature idea backlog for my blog. This felt like a good testing ground for the coding assistants, as it was a bit cobbled together, had gone through a few architectural lurches, but I had written enough of the codebase myself to evaluate the results.

Also, being a blog, the stakes were low. Every time I'd have some idea for the blog I'd jot it down in Apple Notes. Here was what I had built up:

It was quite a decent chunk of work in my book.

These notes were originally just for my own reference, but you'll notice that at some point I started editing the notes with a basic structure for Claude Code that I felt was clearer.

I thought I'd make good headway on a few of them, but over the Christmas break I steamrolled every one of them, iterated on a few, and even added some extras once I ran out.

I started out just about coming up short on Claude limits, having to wait 30 minutes or so before starting again. But by the end of this process I was smashing through those limits really quickly, and had to start getting more targeted and careful about what I wanted to work on.

Eventually though, I was paying extra usage on both Copilot and Claude Code, still cheaper than springing for a higher usage plan, but chafing at the limits.

#The Yegge Inflection Point

This month, I finally sprung for Claude Code Max – though only 5x, not yet the 20x. It's just too powerful an upgrade on my capabilities as a developer to pass up. Other people can wait to see where it goes and look back on this period with sagacity and the wisdom of hindsight.

I am still using Claude Code interactively in VSCode, I haven't gotten to the stage where I never read the code that's being produced, though maybe I'll get there, too. Steve Yegge is there with a few other people, and they are probably living in a version of the future, but it's not the only version of the future.

There are lots of different kinds of software. Not all of it will be amenable to this style of development.

For a 20 year old aspiring software developer in college, I have no idea how they are going to get to their version of mastery For want of a slightly less pretentious term. Basically I just mean skilled and experienced enough to be useful at their craft. Being able to dive deep, take responsibility, adapt and learn on the fly.

For me, it's exciting. If at the end of the day all I end up with is a bunch of completed side projects, it will have been money well spent.